- Update for September 2, 2016: Miami Beach Mosquitoes Test Positive for Zika Virus

- Update for August 2, 2016: CDC Issues Travel Warning during Miami Zika Outbreak

- Update for May 11, 2016: Zika Virus Detected in Asian Tiger Mosquitoes – Puts Northern US in Danger of an Outbreak

- Update for April 29, 2016: First U.S. Zika-Related Death Reported in Puerto Rico

- Update for April 12, 2016: ZIka is a Threat to Adults

New information on the Zika virus is being released frequently. Check back here for updates.

Zika Virus: Here's What You Need to Know

The Zika virus is one of several tropical diseases spread by mosquitoes. The world has seen a strong increase in the number of infections and complications involving this virus since 2015, especially in parts of South and Central America — particularly in Brazil. The virus is closely related to the West Nile virus, dengue, and yellow fever. The Zika virus was in the news frequently in 2015, and continues to dominate headlines in 2016, mostly because it has been linked to microcephaly, a rare but serious birth defect. Pregnant women who are bitten by a mosquito carrying the Zika virus have a risk of birth complications — including microcephaly. In late 2015, Brazil declared a state of emergency because of the virus, which caused many other nations to become concerned about the safety of their own people. In late January 2016, the World Health Organization considered declaring the Zika virus outbreak an international health emergency.

Why do mosquitoes cause so many illnesses?

West Nile virus, malaria, and other diseases can all be spread by the bite of a mosquito. In fact, the mosquito is considered one of the most deadly creatures on earth. Part of the reason for this is its bite. Female mosquitoes need blood when they are getting ready to produce eggs. While mosquitoes only take a tiny amount of blood, they tap directly into our bloodstreams, meaning they can pass microbes back and forth between victims, easily spreading infectious diseases and viruses.

History of the Zika virus

The virus was first discovered in Uganda in 1947, in a forest known as Zika. Since then, the virus has been common in Asia and Africa. However, it has not traditionally been associated with microcephaly. This is partly because outbreaks of the virus didn’t happen in larger populations. In addition, since microcephaly is rare, no noticeable spike in the number of affected births were found. Compared to life-threatening mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria, the Zika virus seemed relatively minor since most patients didn’t even require hospitalization. Then, in 2007, the virus began to spread — first to small islands in the Pacific. By 2013, an outbreak of the Zika virus occurred in French Polynesia. The virus was on the move again, and this time 42 residents out of the 270,000 in French Polynesia had developed the rare Guillain-Barrê syndrome, a condition causing paralysis. It was the first time scientists recognized that the Zika virus could lead to very serious complications on a grand scale, and the first time they saw the virus affecting the brain and nervous system. In May 2015, another outbreak happened in Brazil. It was the first time the virus was seen in significant numbers in the Western Hemisphere. It was also the first time the virus was linked to high instances of microcephaly.

What are the symptoms of the Zika virus?

Symptoms of Zika virus are generally mild and usually last no longer than a week. Most patients do not need to be hospitalized, and the virus is very rarely fatal. Although everyone reacts differently, the most common symptoms are:

- Fever

- Joint pain

- Red eyes (conjunctivitis)

- Rash

- Headache

- Mild flu-like symptoms

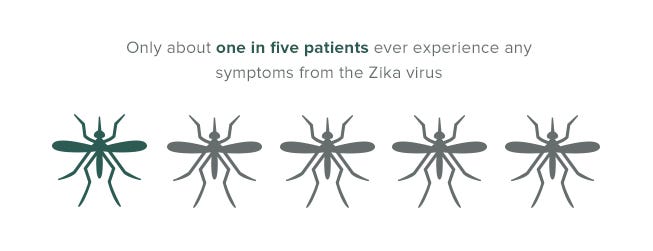

One of the challenges with Zika virus is the lack of symptoms. Some patients have such mild symptoms they don’t even realize they have been affected, and only about one in five patients ever experience any symptoms. In most cases, the incubation period for the virus is likely no more than twelve days, and symptoms usually pass in seven to ten days without any need for medical assistance.

How does the virus spread?

The virus is spread through the bite of a mosquito. A mosquito will bite someone who has the virus, and will then become a carrier itself. If the affected mosquito then bites a healthy person, that person will contract the virus. Not all mosquitoes act as carriers. The culprits are yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) and Asian tiger mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus), distinctive for the white stripes on their bodies. These insects are more likely to bite in the daytime, when many people don’t expect mosquitoes to be active. Only the females of these species bite.

Although the virus is most often spread from an infected mosquito to a healthy person, scientists think it may be spread other ways as well. For example, it may be spread from a mother to her unborn child, and there is some evidence that it may be spread through sexual contact or even blood transfusions, although more information is needed about this. Scientists agree that the vast majority of cases are contracted through mosquito bites.

The Zika virus outbreak and your risk

While the symptoms of the virus are mild compared to malaria and other mosquito diseases, the Zika virus poses a significant threat to pregnant women because it can cause birth defects. Specifically, when a pregnant woman is bitten by a mosquito and contracts Zika fever, her unborn child is at an increased risk for microcephaly and, possibly, other birth complications as well. Microcephaly is a birth defect leading to delayed development, brain damage, cognitive problems and a very small cranium. In some cases, people with microcephaly have a reduced life span and most are permanently disabled. Since the condition affects the development of the brain, some babies born with microcephaly die within a few days, simply because their brains have not developed to the point where life can be sustained. There is currently no vaccine for the disorder, and there are few ways to prevent it other than reducing the number of Zika virus infections among pregnant women.

The effects of the Zika virus

In 2015 and 2016, many of the babies affected by microcephaly likely caused by the Zika virus were born in Brazil, which has suffered a Zika virus epidemic. The virus has spread throughout Central and South America and the Caribbean, although many other countries in warmer climates around the world are potentially affected. Researchers are not certain what the link is between microcephaly and the Zika virus, nor do they know how the virus leads to microcephaly. However, it’s hard to argue with the facts: in Brazil, an outbreak of Zika virus has been linked closely with unusually high numbers of microcephaly.

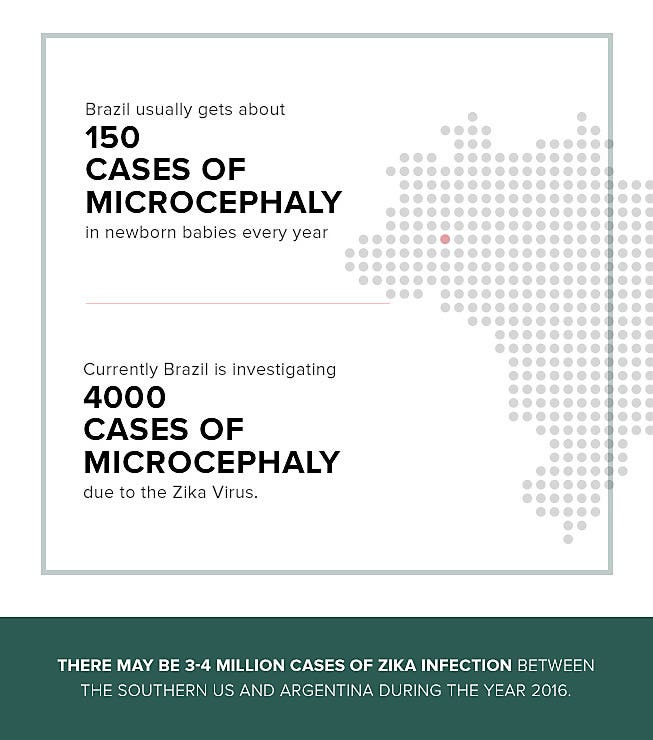

Usually, Brazil reports 150 cases of microcephaly out of the approximately 3 million babies born each year. Between May 2015 and early 2016 alone, however, when an outbreak of the Zika virus occurred, about 4000 instances of microcephaly were reported. In the town of Pernambuco alone (population 9 million), there are usually 9 cases of microcephaly and 129,000 births reported each year. Between May and November 2015, the town reported 646 babies born with microcephaly. In the United States, one child born in Miami in January 2016 was diagnosed with microcephaly linked to the Zika virus.

Where is the Zika virus now?

Due to the risk to pregnant women, the CDC has recommended that pregnant women avoid traveling to countries where the virus is endemic. In January 2016, this included Brazil, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Suriname, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Venezuela, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, and Puerto Rico, although over time, more countries may be added to the list.

If you must travel where the virus is active, or if you are not yet pregnant but are considering getting pregnant, talk to a doctor first. If you are bitten by a mosquito, contract the virus, and then get pregnant, the virus may still be in your system, causing potential risks. In addition to the threat of microcephaly, the Zika virus can cause other complications, such as Zika infection. The Zika virus can be passed from mother to unborn baby, and babies may suffer from Zika infection, which can affect their hearing and their sight, even if they don’t have microcephaly.

If you must travel where the virus is active, or if you are not yet pregnant but are considering getting pregnant, talk to a doctor first. If you are bitten by a mosquito, contract the virus, and then get pregnant, the virus may still be in your system, causing potential risks. In addition to the threat of microcephaly, the Zika virus can cause other complications, such as Zika infection. The Zika virus can be passed from mother to unborn baby, and babies may suffer from Zika infection, which can affect their hearing and their sight, even if they don’t have microcephaly.

The Zika virus in the US

As of early 2016, no one had contracted the Zika virus from mosquitoes in the United States, but between 2015 and 2016, several travelers had returned to the United States with the fever after contracting the virus in affected countries. Between 2015 and late January 2016, approximately 31 cases were reported across 11 states and the District of Columbia. In addition, one case was reported in the American Virgin Islands and 19 in Puerto Rico. However, a forecast suggests there may be 3-4 million cases of Zika infection between the Southern US and Argentina during the year 2016. A few instances of Zika virus among travelers have also been found in Canada. However, Chile and Canada are the only two regions in the Americas where the virus likely won’t gain a foothold, because the climates aren’t sustainable to the mosquitos carrying the virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) believes the United States is at risk for a Zika virus outbreak, since the mosquitoes carrying the virus have been emigrating to certain parts of the country — especially California. The United States has the climate to support these mosquitoes, and they have already been spotted in 12 California counties.

What can pregnant women do if they have been exposed?

The rules for at-risk pregnant women have been changing since 2015 as new information has become available. The CDC initially recommended that at-risk pregnant women receive blood tests to screen for the Zika virus if they had traveled to areas where the virus was active. Unfortunately, this poses a few problems:

The rules for at-risk pregnant women have been changing since 2015 as new information has become available. The CDC initially recommended that at-risk pregnant women receive blood tests to screen for the Zika virus if they had traveled to areas where the virus was active. Unfortunately, this poses a few problems:

- Laboratories do not have the resources to test all potentially affected women.

- Women may not realize they are at risk (because they don’t have symptoms or don’t notice a mosquito bite).

- The risk between the Zika virus and pregnancy is not entirely understood, meaning there may be a secondary infection or something in addition to the Zika virus causing birth defects. In which case, a test for the virus alone may not be enough.

- The location of the Zika virus may change over time, potentially affecting who may be at risk.

- Blood tests for the Zika virus are only accurate within the first week of infection. After that, other antibody tests may be less accurate.

Women who may be at risk are encouraged to get ultrasounds to check fetal development. Microcephaly can usually only be detected towards the final stages of the second trimester, however, which means that women may learn of the condition but have few choices, especially since there is no cure or treatment for microcephaly. Another complication with pregnancy is researchers’ belief concerning when infection occurs. Scientists believe pregnant women are most at risk from the Zika virus during the first trimester. Unfortunately, many women might not realize they are pregnant at this stage, and therefore may not realize they are at risk.

What can I do to protect my family?

Currently, there is no treatment and no vaccine for the Zika virus. Since the disease has traditionally not been very dangerous and doesn’t usually result in hospitalization, there has been little push to develop vaccines or medications. With new links to microcephaly, there is some growing concern about how to keep people safe.

If you are worried about the Zika virus, there are a few things you can do:

- Get the facts. The biggest risk is to pregnant women, and most people outside this group may not even experience symptoms if they’re bitten by a mosquito carrying the virus. If you are not pregnant and not planning on getting pregnant, this disease probably does not pose a risk to you as long as you are generally healthy.

- Be cautious about your travel plans. If you are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant, try to avoid areas where the virus is active. Check for up-to-date reports about the spread of the virus and be aware that any countries where the yellow fever mosquito and Asian tiger mosquito live are a risk — even if an outbreak has not yet been reported in the area. Talk to your doctor before you travel.

- Wear long-sleeve shirts and long pants when heading outside. This is especially important during the day when the yellow fever mosquito and Asian tiger mosquito are most active. Try to avoid swampy and wet areas, where mosquito breeding grounds are most common.

- Stay inside. Keep the air conditioning on, and make sure mosquitos stay outdoors where they belong. Use screens on your windows and doors to protect yourself against mosquitoes. Use mosquito nets at night to provide further protection.

- Use insect repellant. Look for insect repellants with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registration, which ensures effectiveness and safety. Always follow the instructions on the package when using these products.

- Reduce mosquitoes where you live. Mosquitoes don’t just spread the Zika virus, but also many other viruses and diseases. If you live in a warm climate or a four-season climate where mosquitoes thrive, work to reduce the number of mosquitoes buzzing near your home. This will reduce your risk of bites. You can reduce mosquito breeding grounds by mowing your lawn, keeping hedges trimmed, and by eliminating all standing water on your property.

Reducing your risk of mosquito bites

Reducing your risk of any mosquito diseases, including the Zika virus, begins with decreasing your chances of getting mosquito bites. If mosquitoes don’t bite you, you won’t be at risk. Additionally, the fewer mosquitoes you have in your area, the lower your risk of bites. One way to control mosquito populations where you live is with mosquito traps. Mosquito Magnet® mosquito traps, for example, are based on extensive research and are scientifically proven to control mosquitoes effectively and safely over specific areas. This long-term solution converts propane into a mixture attractive to mosquitoes: a precise blend of CO2, moisture, heat and a secondary attractant. When female mosquitos approach the trap, they’re sucked in with a vacuum and deposited in netting, where they dehydrate and die within 24 hours. With fewer female mosquitoes in your area, there are fewer of them to breed, helping to reduce the mosquito population over time.

Want to Know More?

Are you taking steps to protect your family from mosquito bites? Tell us about it by visiting the Mosquito Magnet® Facebook page. If you’d like to do more to reduce mosquitoes on your property, or would like more facts about our mosquito traps, contact us by calling us at 800-953-5737 or by visiting our website. Get the latest news about mosquitoes and mosquito prevention by signing up for the Mosquito Magnet® newsletter.